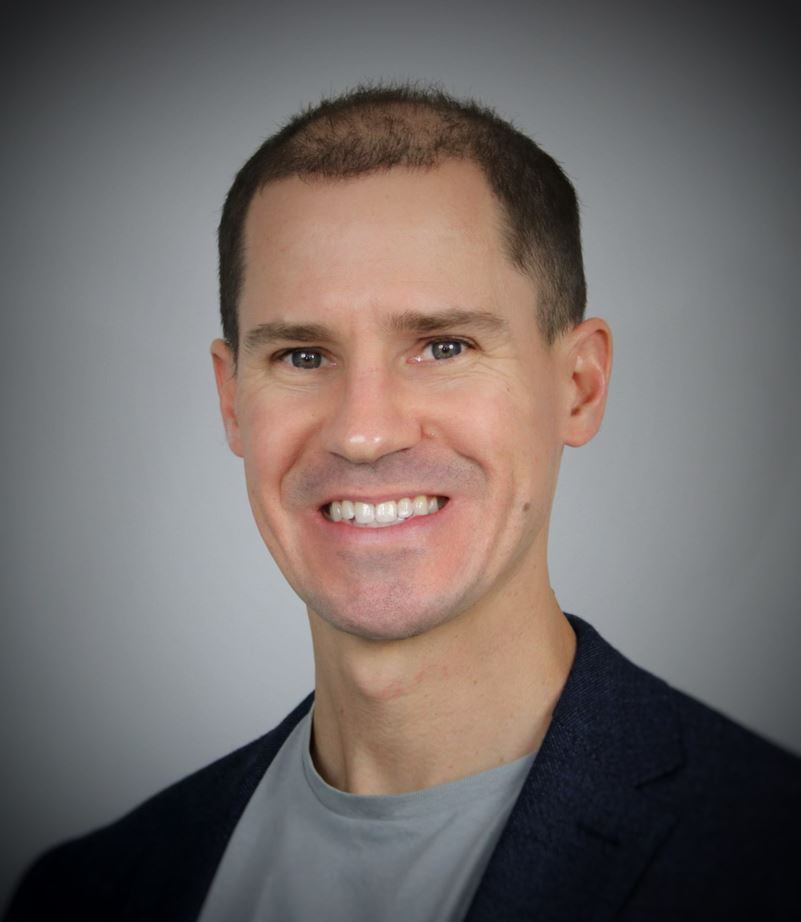

Dr Steven Lewis, education policy sociologist and senior research fellow at Australian Catholic University, believes the “wall-to-wall” coverage of high-achieving school leavers – most with scores of 99.95 and above – pushes a narrow and largely unattainable idea of success and sets teachers up to feel they’ve failed.

“To have such a highly publicised viewing of 99.95 ATAR students in the papers and in the media, on radio and whatnot, it’s really difficult for [educators] not to internalise that as the mark of success,” Lewis tells EducationHQ.

“It’s very difficult to not assume that if the students in [their] care didn’t get 99.95, then [they’ve] somehow failed … it’s an unfair expectation, it sets us up for disappointment, really.”

Among the headlines from late last year featured: ‘Practically perfect in every way: The students kicking honour roll goals’, ‘No way, no way’: Beautiful moment students told of perfect ATAR score’, and ‘Meet the duxes of 2023’.

According to Lewis, the whole ‘nuance and complexity’ of schooling is lost in the media’s skewed focus.

“We’d be remiss to not also acknowledge that it puts a lot of pressure on the teachers who are teaching these students, because in many ways that score, that ranking, is not only representing the success of the students, but by proxy it’s representing the success of the teacher.”

One senior secondary teacher from Melbourne told EducationHQ that Year 12 teachers do seem to base their efficacy on the number of their students that achieve study scores over 40, and not on the learning growth they’ve seen over the year.

“You receive a pat on the back when (high) scores over 40 come through, but schools don’t tend to celebrate students who made significant learning growth through the year and achieved say a 30,” she says.

For senior students, plentiful stories sharing the ‘perfect’ achievement of a select few delivers the wrong message about what it means to succeed and the options available to those that fall short, Lewis argues.

“It really does present the message, in my mind at least, that if you’re not getting [the perfect score] you’ve somehow failed or you haven’t maximised the opportunities you had at school.

“And I think when you do that, it sends the message that there’s only one way to be successful once you finish Year 12. And I think that is demonstrably not true.”

For starters, a perfect score can only be attained by a very small percentage of students across the country.

“Even if everyone maxed all their grades, and got 100 per cent on all their tests, they still couldn’t all be at 99.95. So, you’re emphasising something that will only ever be available to a handful of people,” Lewis says.

“But I think the more substantive issue is that [these stories] suggest that somehow students who don’t get 99.95 are really disadvantaged, or are going to miss out on opportunities post Year 12.

“I don’t think that’s a particularly helpful thing to put forward…”

Dr Steven Lewis says the media should focus on lowering the 'collective temperature' around ATAR results.

The expert is keen to point out that success is not a one-size-fits-all concept in education.

“If you’re from a very socioeconomically advantaged family, where everyone in your family has gone to university and has got professional careers, and you know how to navigate the system, then getting into law or medicine at a prestigious university might be success for you.

“Alternatively, if you’re the first person in your family to go to university, to finish Year 12, or you’ve got lots of family issues, socio-economic disadvantages, or you don’t speak English as first language ... success might look different.”

Social media has also fuelled the public ATAR frenzy, Lewis notes, with ecstatic student ‘reaction videos’ attracting millions of views on platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

“It’s just one more string to the bow of adding undue pressure to our young people,” he adds.

Although not wanting to downplay the importance of the ATAR and the very real anxieties that can often surround it, Lewis says it pays to bring some perspective to students’ understanding of the ranking system and remind them of the multiple pathways into their chosen field should they not get the score they hoped for.

“Once you leave (school) the importance of ATAR very quickly recedes into the rearview mirror ... it doesn’t mean that pathway or that option is forever closed to you, it doesn’t reflect necessarily where you’re going to end up.

“As soon as you get into the workplace, or as soon as you get into university, once you’re there, no one’s asking what your ATAR is – nobody is asking me now, as a university professor, what I got at the end of Year 12.”

Yet the expert cautions the media’s feverish output of ‘practically perfect’ stories is not solely to blame here.

“The media ... is responding to the pressures and the conversations that other people are having, as much as extending those conversations.

“So I think if we as a society want there to be less undue pressure and stress placed upon our young people around the ATAR, around NAPLAN or any of those big ‘high stakes’ assessments, then we also need to change the way we have those conversations,” Lewis says.